Sudan, Remember Us, and True Chronicles of the Blida Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in the Last Century, when Dr Frantz Fanon Was Head of the Fifth Ward between 1953 and 1956

Before the Gezi Uprising in Turkey there was the Arab Spring, first Tunisia went to elections and then Egypt changed its ruler who crushed the Revolution, killed and imprisoned many of the revolutionaries. Syria was thrown into a civil war. Then later in the decade came the Sudan Uprising in 2019 that erupted from the same fountain of resistance that stirred jubilation among those resisting, breaking the fog of silence that is mistaken for obedience.

The cinematic works on these periods are contributing to the visual archives of these popular uprisings as aesthetic reflections. I recently watched Sudan, Remember Us (dir. Hind Meddeb, 2024) at the Alfilm Arab Film Festival in Berlin. It is a beautiful, thoughtful, poetic documentary that takes the viewer to the encampments during the time when people went out on the streets of Sudan to oppose military rule and demand dignity. The documentary does not focus only on the popular protests like many other documentaries that came out of the popular uprisings of this decade. Instead, it frames the joyful resistance as it erupts from the depths of the history of resistance in Sudan, passed on to those whom we see chanting the poems of long dead poets of Sudan. The film is less motivated in chronicling an uprising, and its violent suppression, then showing the continuity of the experiences and wisdom of the past struggles through songs, poetry, in the young people’s genuine acts of claiming them. There are murals paintings of long-dead revolutionary poets whose poems are recited by these protesters, and there is another line of mural depictions of those who were killed by the state security officers or their thugs, in which the painting are done collectively, followed by a solemn gathering and food sharing. The Sudanese revolutionaries are critical about the instrumentalization of the faith by corrupt Imams but it does not mean the foregoing of all religious, communal traditions. I recognize the ingenuity of their way of reclaiming of faith from an egalitarian perspective with a revolutionary emphasis on freedom, that resonates with my experiences at the Gezi Park during the summer of 2013.

The director of Sudan, Remember Us, Hind Meddeb, is a French-Tunisian-Moroccan journalist and documentary filmmaker. She has close relationship with some of the protagonists of the documentary and this is clear from the proximity of the camera that is invited as a co-conspirator to the conversations such as deliberations about the current situation at the time, like when the women meet after the overthrow of Omar al-Bashir at a coffee or tea shop. There are also scenes of streets with a tilted angle taken at night from a window and of buildings across the street from indoors, accompanying the off-screen voice of women reading letters that are exchanged between the director and one of the protagonist. There are also shaky scenes of running from the security on the streets. Such footage suggest the collective nature of film making, sometimes using found footage, as it is true for some documentaries made during or right after uprisings. I have in mind, for instance, Love will Change the Earth (dir. Reyan Tuvi, 2014).

Sudan, Remember Us is like an insider story. It will not make the audience learn about the Sudan Uprising, but it might help to understand it. It is a heartful eulogy, and a solemn remembering of those who had put their bodies, heart and soul, out in harm’s way, daring for imagining a just world, another society in which people are equal and free. The documentary for me was also a reminder of those moments of freedom to imagine that future.

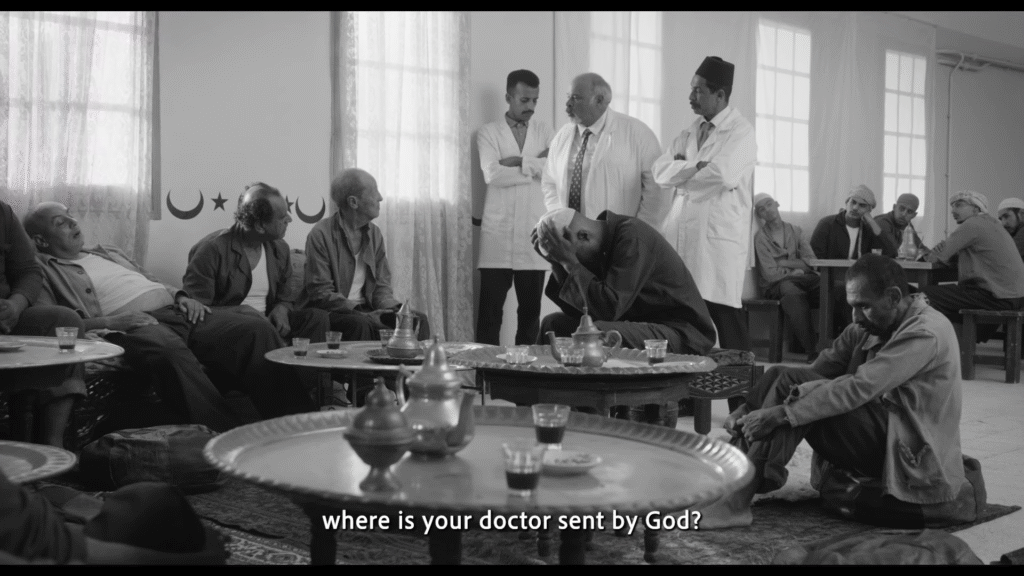

The other film that I was very happy to have been able to watch at the Festival has the longest name I have encountered for a cultural work: True Chronicles of the Blida Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in the Last Century, when Dr Frantz Fanon Was Head of the Fifth Ward between 1953 and 1956 (dir. Abdenour Zahzah, 2025). It is a fictional, B&W film on the “true chronicles” of the Blida Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria, between the years 1953 and 56, when the famous author Franz Fanon worked there after being appointed by the French government, that was ruling over Algeria at the time. The film chronicles Fanon’s encounter with the old school of treatment at the hospital as well as the colonial conditions in Algeria, that became the bedrock of Fanon’s writings. For those familiar with his work, Fanon’s encounters and interventions will be familiar. During the extensive Q&A session with the director Abdenour Zahzah after the screening, who researched and wrote the script of the movie, told the audience that the making the film included the coordination with the present director of the hospital, who had been there at the time of Fanon, who also voluntarily supervised the writing of the script. Apparently, Fanon had kept journals during his time at the hospital, not only taking notes related to his patients, but also about everyday life at the hospital, the relations between staff and patients, the customs of the hospital, and even noted down funny events. The film came into being through the use of such archival material that is only accessible to researchers.

The film is for me also a great example of how fictional works can also be meticulously factual and I see it as an important contribution to the study of Fanon. It creates a window into an important period in Fanon’s life, as he explains in the film, while he worked with Algerians in France, he had not seen life in Algeria and what colonialism meant for those living there. The film is not trying to tell a developmental story of Fanon or create a big narrative about Algerian liberation movement. On the contrary, it maintains a very cool tone of storytelling with heartwarming insights, that is both serious, sympathetic, and political.

I wish that more people would become aware of both of these films and that the films find wider audience in many languages.